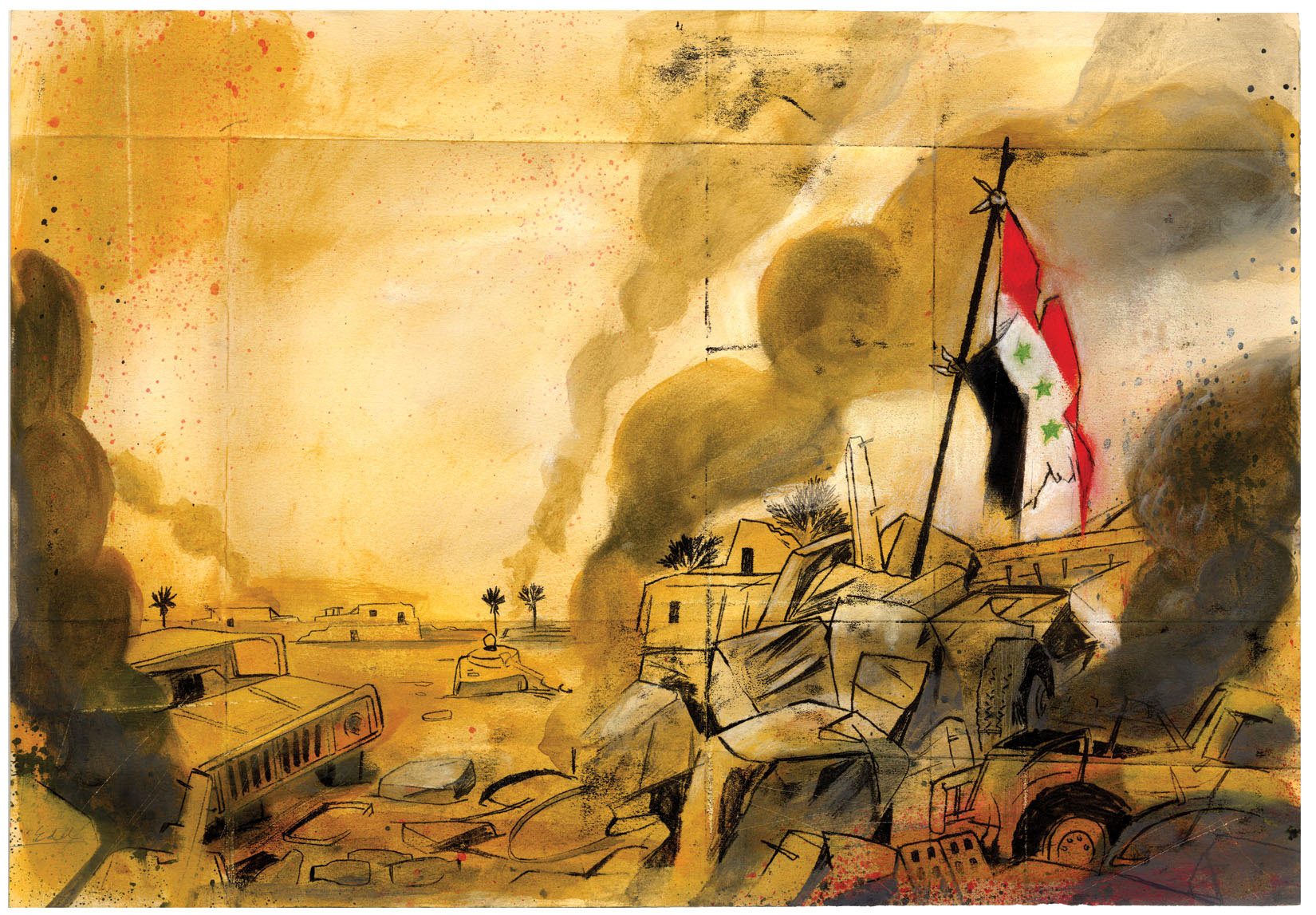

With the apparent conquest of Iraq’s northwestern provinces – and maybe more – by the militant Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the country’s troubled history has opened a horrifying new chapter. In a matter of just days, ISIS’s fighters overran Anbar, Ninewa, and Salahaddin provinces – a victory that attests to the central government’s non-existent authority in Sunni-majority areas. And, given ISIS’s jihadi ideology, there is limited scope for “Sunni outreach” – the supposed panacea for all that ails Iraq’s sectarian political culture.

ISIS is not a group that is receptive to dialogue. Its leadership adheres to the view, expressed in many corners of the Arab Sunni world, that Shia Muslims are apostates and betrayers of Islam who rank among the worst of the worst (alongside Israel and the United States). This means that the US needs both a military response to ISIS and a political response that extends beyond Iraq. What is needed, above all, is a regional approach to the increasingly murderous Sunni-Shia rivalry.

[quote text_size=”small”]

It is worth remembering that the original sin of the US-led occupation of Iraq 11 years ago was so-called “de-Ba’athification” – the purge of any and all people with ties to Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath party. That decision was taken in the year following the 2003 invasion, when Iraq was a wholly-owned US subsidiary; Iraqi officials, whether Shia or Sunni, had almost nothing to do with it.

[/quote]

It is often said that Iraq needs a Nelson Mandela; the same could be said of US policymakers back then. In the ideologically charged US policy circles of the time, de-Ba’athification was understood to be a decisive move to extirpate a heinous ideology. It was likened to the de-Nazification of Germany following World War II.

But de-Ba’athification ended up targeting anyone who ever had ties to Ba’athism, something far beyond what the occupying armies attempted in Germany. Given the vast patronage system that Saddam had created, such people included even elementary school principals. And, though some Shia, especially secularists, joined the Ba’ath party to survive in Saddam’s system, Ba’athism was broadly and correctly understood to be a kind of secular fig leaf for Sunni minority rule.

Thus, the overall effect of this de-Ba’athification program was to marginalize the Sunnis. And the Sunni response to de-Ba’athification became de facto support for Islamists.

That is where we are today. By and large, Iraqi political parties are sectarian organizations. Shia vote for Shia candidates and Sunnis for Sunnis. There are exceptions, of course. Following April’s general election, not every Shia is delighted by the prospect of another term for Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki; but they were not prepared to vote for Sunni parties to prevent it.

US President Barack Obama is correct in saying that a political complement to any military action is needed. A good place to start probably would be a pledge by Maliki not to lead the government for what would be his third term. Maliki has become the most polarizing figure in Iraqi politics, and it is difficult to imagine the country making any progress under his leadership.

But there needs to be a far more concerted effort to persuade Iraq’s Arab neighbors to accept a Shia-governed Iraq. Among Iraq’s Arab population (that is, leaving aside the Kurds, who make up roughly 20% of the population), Shia outnumber Sunni by three to one. In a country where political identity is – at least for the time being – tied to sectarian identity, majority rule thus means Shia rule.

And yet the rest of the Sunni Arab world has had a difficult time absorbing this demographic fact. Many countries – for example, Saudi Arabia – have restive Shia minorities, and one, Bahrain, has a restive Shia majority.

But all Sunnis should be concerned about the kind of extremism that ISIS represents. Though the bombing and assassination campaign waged by Sunni Islamists in Iraq has been directed mainly against Shia, many such attacks have also targeted Sunnis suspected of supporting the government. And much of the weaponry and other aid that Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states have supplied to support the Sunni uprising in Syria is now in the hands of extremists. It turns out that arming Syria’s moderate rebels is easier said than done.

What is happening today in Iraq is part of a broader pattern of sectarian violence across the region. Whether triggered by the US-led invasion of Iraq 11 years ago or by the often-misunderstood Arab Spring, sectarianism is alive and well, and, in the case of ISIS, it is accompanied by the kind of terrorism that the US has confronted so firmly since September 11, 2001. America and the West need a policy that addresses the sectarian struggle head-on – not just in Iraq but throughout the region.

Το άρθρο δημοσιεύεται στο www.project- syndicate.org

Christopher R. Hill, former US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia, was US Ambassador to Iraq, South Korea, Macedonia, and Poland, a US special envoy for Kosovo, a negotiator of the Dayton Peace Accords, and the chief US negotiator with North Korea from 2005-2009. He is currently Dean of the Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver.